The breakthrough of Hank Williams was unique. Country crooners were not supposed to be philosophers. Their poetry was not sublime. But the artistry of Hank Williams was different. He may have looked and sounded like a yokel, but the depth of soul in him was something else. His art made him singular and ultimately iconic. Hank showed a new way of singing the blues. He is an American treasure.

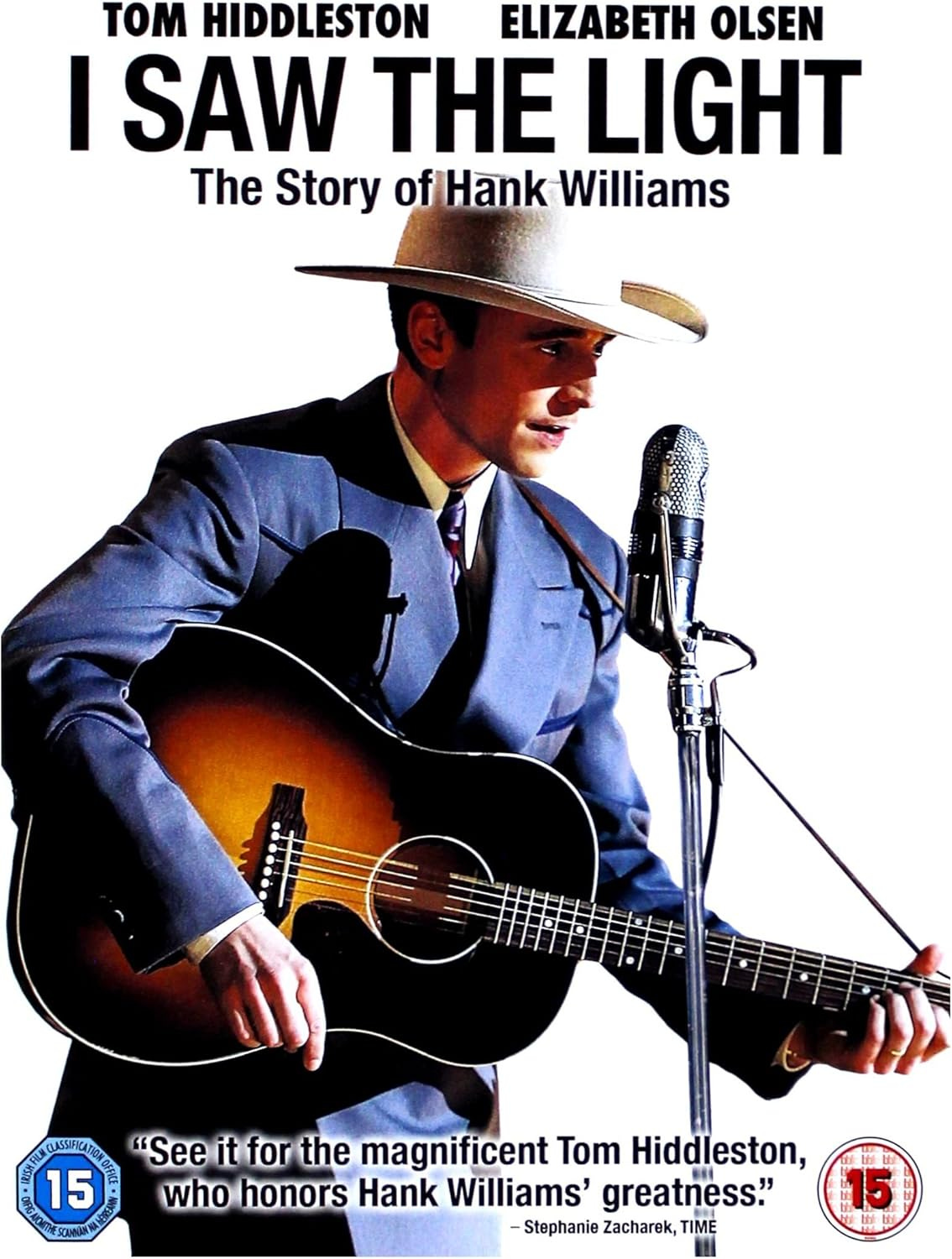

I Saw the Light

Poet of heartache

When I was a boy my dad would sometimes sing me to sleep at night, strumming an old box guitar, singing Country & Western tunes. He did the same for my two brothers and my sister. He played basic chords and his voice wasn’t strong but he sang the simple hard-luck songs with great feeling, as if in song he could better express himself than in life with words. All these years later I can still hear that voice and guitar.

Jim Reeves, the Carter Family, Johnny Cash, Johnny Horton, Marty Robbins. These were some of his mainstays. He loved Patsy Cline too but wouldn’t sing her songs, perhaps thinking it foolish for a man to try. But of all the country singers and Grand Ole Opry stars he loved Hank Williams best.

Hank was born in September 1923, my dad in November that very same year. Exact contemporaries, they survived the Great Depression together, a terrible time of privation that scarred both. My dad pinched pennies throughout his life, traumatized by the fear of destitution. It was an illusion. By the end he was nominally rich. But in his mind he was always poor, always struggling. Hank felt the same. He was the voice of struggle, hardship, loss, heartache. Like every great poet he whittled down feeling to the simplest words. That’s where his profundity lies — in simplicity.

My dad, too, was simple in his ways. He was practical, Germanic in thinking. Chores, hard work, saving, investing. These were the things that got one ahead. God and religion weren’t as important, thank goodness — just social conventions. Rely on yourself and your own hard work, not God. Who knows, whoever proved that the old graybeard was even listening? If I was a freethinker, a dissenter from an early age, it’s because my dad never bullied and threatened me with fire and brimstone. And, thinking back, it’s one of the dearest legacies he left me — a mind free enough to work things out for itself. “Your Cheatin’ Heart”, “Jambalaya”, “Honky Tonk Blues”, “Cold, Cold Heart”, “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry” — he sang and loved them all. Hank touched something deep in him the way he touched millions of others.

Hank had his demons. This is well known. Whiskey, pills, morphine, tobacco: all of it used in excess. He ate and slept poorly. He womanized, ran around on his wife. He had a bad back, was born with it, and it only got worse through time. But his music was honest, his art pure, and that’s why he lives on through it.

In 1951, in New York City, he did the following interview with a journalist named James Dolan (or at least it was framed like this in the film):

Reporter (sitting down with Hank): You don’t like doing this much, do you?

Hank: It comes with the job. You know what I don’t like, it’s people saying one thing when they’ve got something else on their mind. You do what I do, get where I am, you see plenty of that: people thinkin’ they’ll make a nice pie with a slice of me.

R: Well, I’m only looking to give people some insight into you: why you write what you write, sing what you sing.

H: I write what I write and sing what I sing cos that’s what I do. Ain’t much choice, right?

R: As an artist?

H: That’s your word.

R: You are offering your fans something. What would you say that is?

H: Mr. Dolan, everybody has a little darkness in them. They may not like it, not want to know about it. But it’s there…Things like anger, misery, sorrow, shame. And they hear it. I show it to them. And they don’t have to take it home.

R: You think that’s what they expect from you?

H: They expect I can help their troubles…I reckon they think I’m some kinda Red Cross…You can write this down: folk music, hillbilly, it’s sincere. There ain’t nothing phony in it. A man sings a sad song. He knows it’s sad.

Hank came out of that darkness, that sincerity. It’s what he did, what he could do. Cliché and convention didn’t interest him. He sang from experience, the heart. He didn’t fake his way through life and art. If the songs are painful, they say what he felt. How do you write of such things without lapsing into self-pity and parody? I don’t know. It must be difficult. Somehow he could do it.

A line from “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry”:

“The silence of a falling star lights up a purple sky.”

The silence does this, not the light. No country bumpkin could have written this. It comes from a place of suffering in the soul, a place of insight. He wouldn’t have called it art and poetry because those were not his words and meant little to him. It was the feeling that mattered. He sang what he felt, what millions feel. By making it personal he made it universal. His genius was his honesty. The bogus never interested him. There was nothing in that to sing about. All his energies went into the authentic.

The standard biopic begins in youth and ends in death. This one isn’t standard. It isn’t interested in covering the life: the first guitar, band, gigs. All this can be imagined. Instead, it focuses on adulthood and relationships because that’s what Hank sang about: love and its many complications.

Women were central to his existence. His sensitivity came from them. He listened and cared about what they thought. They saw better than men did. They lived more deeply, unafraid of their emotions as men are. They could express them and wanted to. It was like breathing for them, oxygen. Men by comparison were always suffocating, bottled up and suppressed, fighting and brawling and cursing to let it out. Or going to war. Hank knew both sides and preferred the feminine, loved the feeling of being in a woman’s arms in bed, a place of comfort that felt like home. There he could breathe and feel free.

Hank had no father, or not one he could remember. Instead he had Lilly, a dominant mother, the template for women he would love, the strong ones who could hold their own, the ones who wouldn’t be pushed around and bullied by men. He loved them for that, for refusing to be only what men wanted them to be. He hated authority and saw in women a kind of kindred spirit of resistance. Like them, he was an outsider. Like them, he would hold his own, not compromise.

Audrey was his first wife, the main rival to Lilly. They fought over Hank — over his life, art, genius. Each claimed him and neither was willing to give an inch without a fight. Audrey was ambitious. She had a good head for business (unlike Hank) and wanted to be a singing star too. Country girl that she was, she loved country music. Problem was, her voice wasn’t nearly as good as she thought it was. Hank and Audrey, the duo she dreamed of, was never going to happen. She might have been able to match Hank’s stage persona, his innate charisma, his willingness to please others in song. But she couldn’t write and deliver as Hank could. There was only room for one star on stage and it was obvious to all, if not to her, that it would be Hank, not her.

Their time together was passionate and turbulent. The love was real but highly complicated, complications that made his songs great. Without Audrey, or one like her, such songs could not have existed. “Cold, Cold Heart” is a portrait of what Hank felt when things fell apart. It is his errant love sonnet to her.

The film is faithful to what he went through: the first radio sessions, the first hit (“Lovesick Blues”), the first night on the Grand Ole Opry stage in Nashville. In between, bars and hamburger joints, cars and the highway, cheap motels, hospital rooms, stages to perform on. As time went on he became the dancing monkey on stage, the thing the world demanded. They didn’t see him that way, but he felt it. He felt everything acutely.

It wore him down and out. He was always thin and frail. The body couldn’t match the heart and soul. He burned brightly but it couldn’t last. It burned itself out when his heart finally gave out, aged just 29. But you can’t measure what happened to him or what he did in years. He lived by another time standard. Fast and furious, as they say. The arc he took is the one he had to. “Ain’t much choice, right?” That’s what he told the journalist in New York. He couldn’t say no to his fate.

Where is Hank in Leonard Cohen’s famous “Tower of Song”? He’s at the top, 100 floors above Leonard. Really? How could Leonard place him so high? Because Hank is the start of all things, the Book of Genesis in modern music: Chuck Berry and Eddie Cochrane and Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis before they were who they were. Elvis before Elvis. The Beatles before the Beatles. Leonard knew this. His poetry and novels would not sell. He couldn’t eat and pay his bills. So he picked up a guitar, learned a few chords, was on his way to Nashville from Montreal when he got sidetracked in New York City. Dylan, Ginsburg, Joan Baez, Judy Collins and the others changed the trajectory of his own arc. New York for him, as it was for Dylan, would be the defining place, not Nashville. There in the Chelsea Hotel (and in bed with Janis Joplin) he found himself in song. Leonard loved Hank and Country but stayed true to what he really was — an urbane metropolitan, a beatnik and bohemian. Leonard in 10-gallon Stetsons and cowboy boots was a bad fit. It never would have worked, never would have looked right. But for Hank the get-up was everything. It was real and it was him.

All the memories of my dad and youth flooded back as I watched this beautiful film. Others will have their own memories. I was too young to have Hank touch me directly, but touch me he did through someone else who loved him deeply.

Released on Sept. 12, 2016. Running time: 2 hours and 4 minutes.

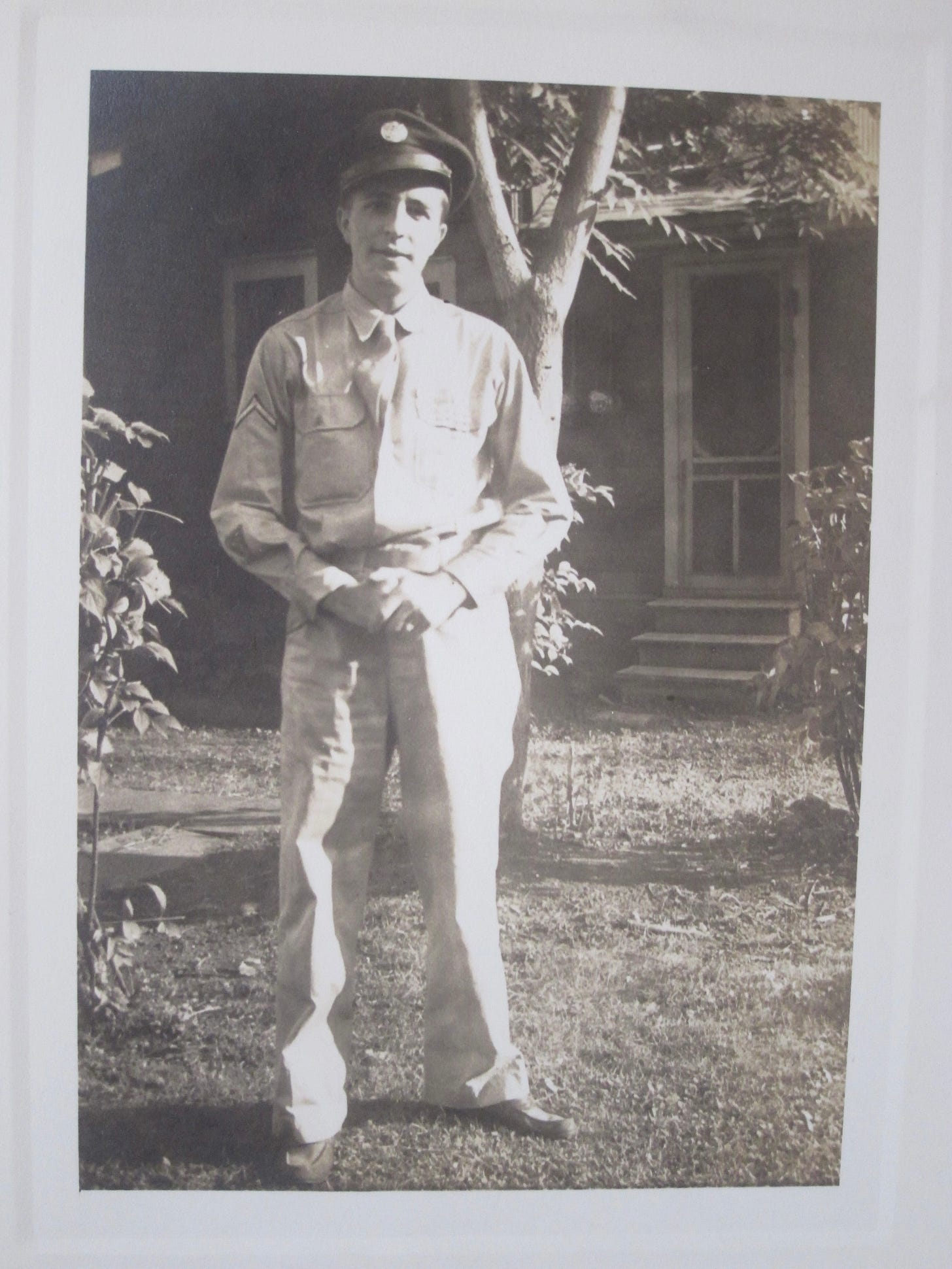

My father as an Army private in World War II, aged 19 in Michigan in 1942. He was thin like Hank and loved Country music. He survived the war in the Pacific behind a desk and typewriter, as he was never in the mood to kill anyone even though the killing had to be done. His survival gave me life, as well as the music of Hank Williams. Hank may have sung for millions, but when my dad sang Hank he sang for me.